Cover Image: Illustration licensed from Vectostock.com

Why it’s not all bad and how to you can remember important information

Did you know that we’re hard-wired to forget? Forgetting is a “tool” we’re equipped with to help with filtering out bad information.

Imagine how dangerous it would be to retain 100 percent of what you learn. You would retain both relevant and irrelevant things. You’d make decisions based on a lot of information that’s irrelevant. By remembering only what the brain qualifies as “relevant”, it filters out what is “useless”.

But what does the brain consider relevant and useful?

In a nutshell, it’s the information it came across many times before. Sadly, this is not a perfect design, but rather a double-edged sword. The brain doesn’t know if something is good for you or not. It thinks the things it perceives the most is what’s relevant.

It’s easy to see this in action. Feed your body junk and your brain will accept that junk is what your body needs. Negatively talk about yourself and your brain will crave negativity. Any dependence or addiction starts with just a few repetitions.

That’s the negative side. But knowing the negative side helps you realize that you can use this as a power to affect the positive side.

How?

As you now know, your brain forgetting is to protect you from misinformation. To judge if the information is relevant, it almost exclusively relies on repetition.

So, should you repeat the same thing over and over for a while or is there an optimal pattern?

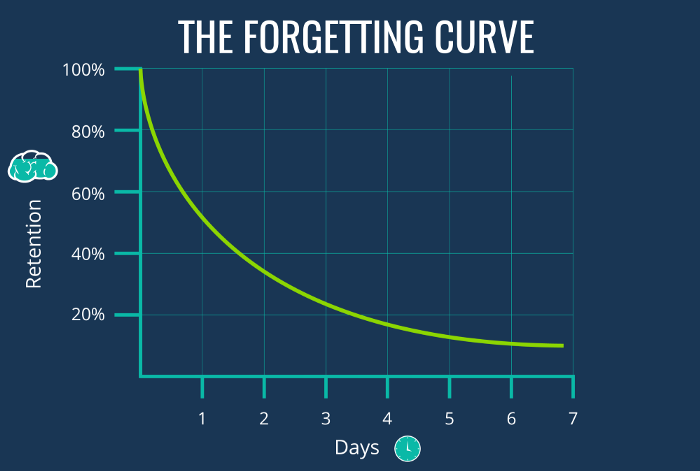

There is! It all starts with an understanding of the Forgetting Curve, a concept first explored by Hermann Ebbinghaus in the late 19th century. The curve shows how information is lost over time when there is no attempt to retain it.

Here’s what it looks like:

If you don’t recall what you learned within the next 24 hours, you could lose up to 50 percent of the information. The good news is, you can fight this off using Spaced Repetition.

For optimal results, recall the information at these intervals:

Immediately at the end of a learning session;

After a day;

After a week;

After a month; and

Sporadically months after.

With every recollection, your brain will start to accept the information as truth and store the information in your long-term memory. Once in your long-term memory, it will be very difficult to forget.

When you choose the right things to feed your brain and use spaced repetition, you’ll have succeeded in retaining things you chose to retain.

But there’s an important pitfall you should be careful not to fall into.

I’m a big advocate of taking notes or creating mind maps. But there’s a potential problem you can probably guess: what if your notes and mind maps are not accurate and you keep on recollecting these bad notes and maps?

Indeed, that’s bad.

If you keep feeding misinformation to your brain, it will accept it as truth. The problem is that it’s very hard to forget something you’ve so deeply recollected and studied. That’s why it’s hard to change someone’s mind about something they’ve had repeated experience with. Their brain has accepted a piece of information as truth and start seeing the world with only that lens.

Takeaway

Feed the right information to your brain enough times and at select intervals and you’ll retain what you learn for life.

You can do this!